The first part of the journey is dedicated to the relationship between the Cathedral of Monza and the Visconti family, covering a time span from 1277, when this powerful family took control of Milan, to 1447, the year of the death of Duke Filippo Maria.

The displayed material wonderfully presents this delicate historical turning point, clarifying the Visconti’s connection with the Basilica of San Giovanni. Their aim was both to firmly establish their power over Monza and to support the claim of their family’s descent from the Longobards, thereby reinforcing the full legitimacy of the power they had acquired.

Welcoming the visitor is a portrait of Giovanni Visconti, the archbishop and lord of Milan, who in 1345 secured the return of the Duomo’s Treasure, which had been moved to the papal court in Avignon in 1324.

To commemorate the event, there is a parchment with an inventory of the valuable items recovered, displayed in a case next to a copy of the Iron Crown and the Bible of Alcuin, a manuscript created in the 9th century in the scriptorium of Tours, chosen to allude to the connection between the sacred diadem and Carolingian culture.

Beyond the display case, two doors of the basilica’s organ, painted at the beginning of the 16th century by the De Donati workshop, depict the scene of the Restoration of the Treasure. In this scene, several attendants place the treasures on the main altar of the church, in the presence of Giovanni Visconti and Saint John the Baptist.

The opposite wall is dedicated to Matteo da Campione, the architect and sculptor who between around 1360 and 1396 designed and created the facade of the new building, the now-missing baptismal font, and the pulpit that still dominates the central nave.

To testify to these works, several slabs are displayed, featuring geometric decorations, figures of saints, religious and secular symbols, as well as some small heads that originally decorated the tops of the spires on the facade.

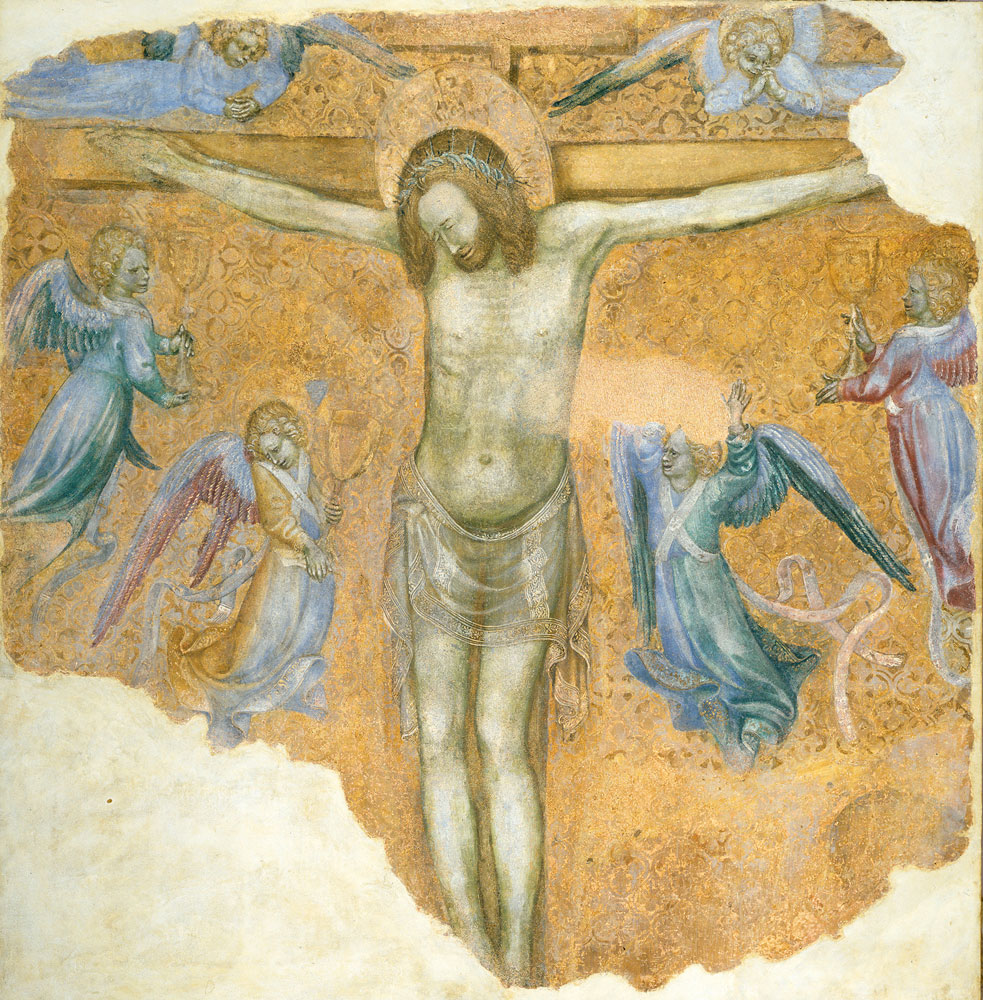

There is also a reference to Theodolinda and the devotion shown to her by the people of Monza, highlighted by a display case containing the remains found in 1941 in the sarcophagus where the Queen’s relics were transferred in 1308. Further, a large fresco depicting the Mass of Saint Michael shows, among the figures depicted, the Longobard queen. Next to this painting, there is a fragment of a fresco depicting the Crucifixion, attributed to Michelino da Besozzo, the Stocco of Estorre Visconti, found with his mummy in a tomb in the cloister, and several late Gothic and Renaissance pieces of goldsmithing, including a masterpiece like the Chalice of Gian Galeazzo Visconti.