With the end of the 18th century, another phase in the history of the cathedral began, as illustrated in the fourth part of the tour.

Between 1792 and 1798, Andrea Appiani created the new high altar, evidenced in the museum by the casts of his magnificent sculptures modeled by Angelo Pizzi based on Appiani’s design.

From 1796, the year the Napoleonic occupation began, the basilica entered a difficult period.

Half of the silver objects and two-thirds of the gold items from the Treasury were requisitioned and sent to the Milan Mint to be turned into coinage, or sent to the museums in Paris, where some were stolen and destroyed in 1804. The surviving items were returned in 1816.

However, following the looting, a new season of donations began, during which the church received collections of ancient works, such as the wooden carvings from Mount Athos donated in 1809 by architect Carlo Amati, or the ancient Italian and French ivories given in 1825 by Countess Carolina Durini Trotti.

Displayed at the end of the path, these artifacts are complemented by elegant neoclassical liturgical furnishings and various objects used in the last coronations, whose allure remains unchanged, starting with the two silver votive loaves made for the coronation mass of Napoleon in 1805, and the velvet and pearl box used to transport the Iron Crown to Vienna for the coronation of Ferdinand of Austria in 1838.

Transferred to Austria after the unification of Italy, the sacred diadem was returned to the Monza Cathedral in 1866 through the efforts of King Victor Emmanuel II.

After declaring it a national relic and symbol of the kingdom in 1883, King Umberto I ordered it to be placed in a new altar, which was specifically built by Luca Beltrami in 1895-96 in the Chapel of Theodolinda, where the queen’s sarcophagus was also placed.

During the same period, Beltrami also oversaw the restoration of the basilica, which was completed in 1908 with the reconstruction of the stone cladding of the facade and the rebuilding of the spires that had been previously demolished, along with their respective statues.

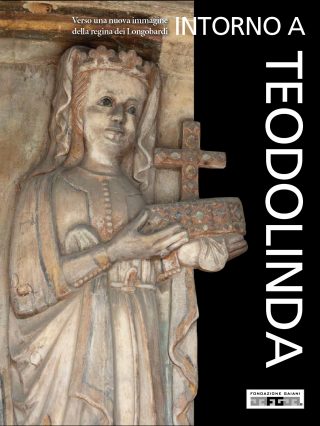

Among them is also the statue of Theodolinda, depicted in the act of donating the Duomo, with its preparatory plaster cast displayed along the path, symbolizing the eternal role that the Lombard queen has played in this extraordinary story of art, culture, and spirituality.

A brief but intense off-program consists of the acquisitions, commissions, and donations that in recent years have continued to enrich the church’s heritage, providing a vivid testimony of the characteristics of contemporary sacred art.

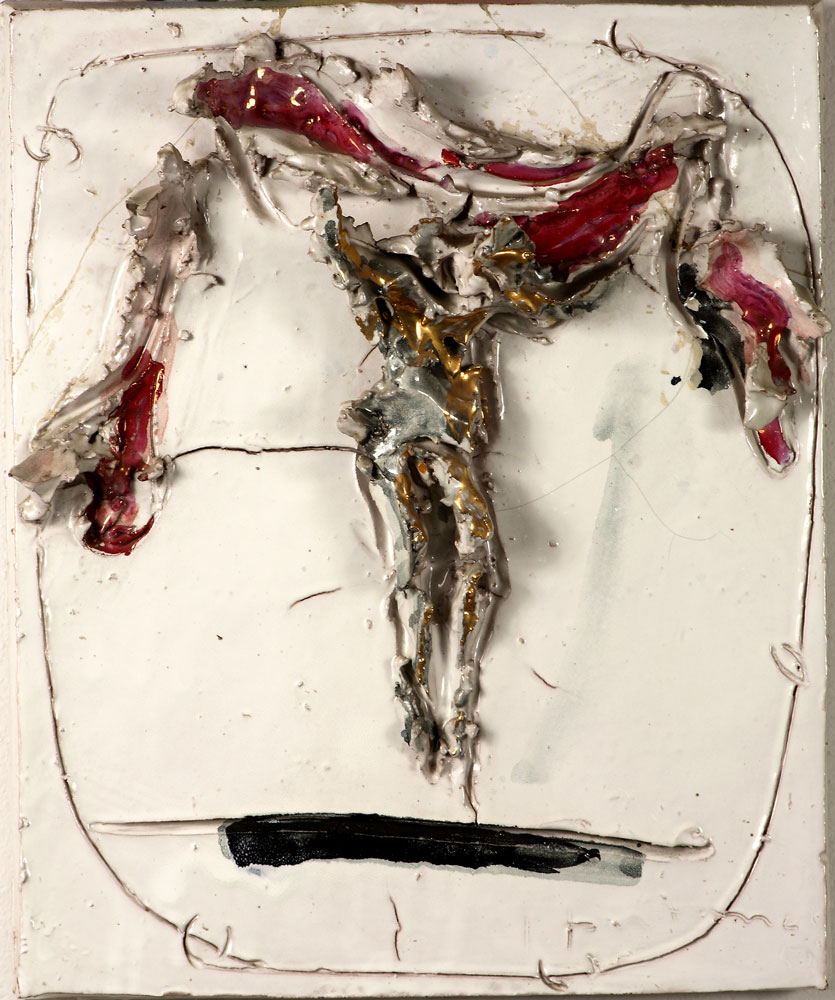

Among the pieces on display, two small sculptures stand out: a polychrome ceramic Crucifixion created around 1953 by Lucio Fontana, the father of Spatialism, and a bronze-cast Risen Christ from 1974 by Luciano Minguzzi, the author of the famous Door of Good and Evil for St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

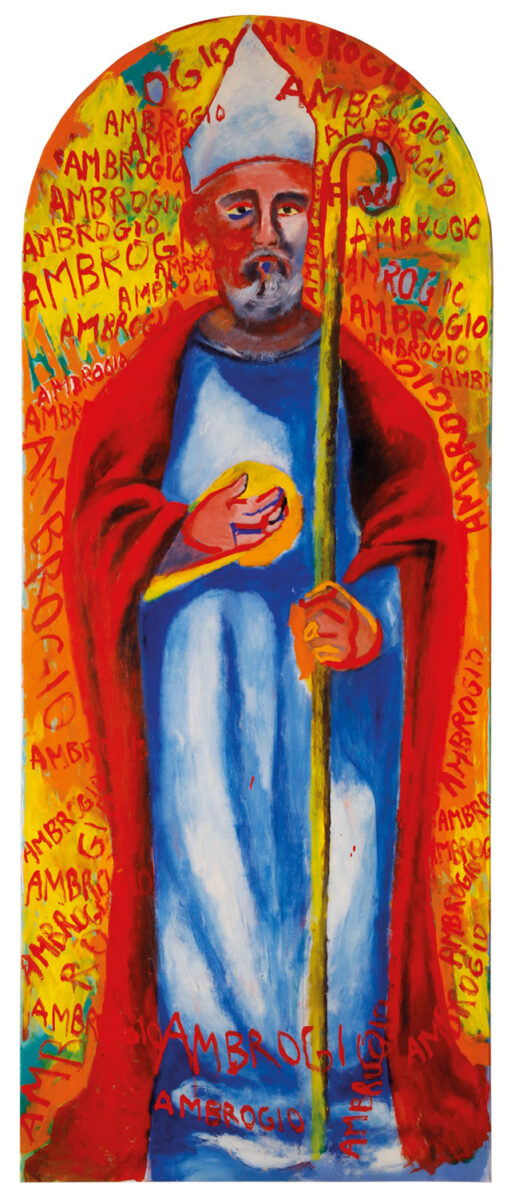

They are accompanied by two large preparatory sketches for the stained glass windows of the presbytery, depicting Saint Ambrose and Saint Charles Borromeo, painted in 1995 by Sandro Chia.